December Notes - 2023

This year could not have been more different from last. 2022 coming out of COVID my dealers all scheduled one-person shows with me. In the meantime, Emily, my assistant, and I were involved with a major “studio edit”, clearing out 45 years of stuff, painting the walls, insulating, moving, and organizing [more about that here]. Then, in October I was told that I needed open heart surgery. Considering what was wrong with my heart, I am lucky I hadn’t killed myself with the heavy lifting I was doing. I was instructed not to lift anything over 15 pounds. Emily even had to carry my purse!

2023 started with no exhibitions on the books and me convalescing from the open-heart surgery at home. I set up a temporary studio in my living room. I wasn’t too physically impaired, I just couldn’t manage to get out of bed by myself, but my brain either from the narcotics or the anesthesia exhibited massive brain fog. I just could not concentrate!

It brought to mind a painting by Gauguin, “Where do we come from? What are we? Where are we going?” Not the painting as much as the title. When you go through controlled physical trauma like this, where all the insane stuff happens while you are unconscious, you awaken into both the fog and clarity of your narcotic brain, with your heart beating no longer with the universal thump-thump, but rather with the sound of a single finger tapping on the taut skin of a drum, your body now joined with that of a cow, you do start to ask yourself – Where do I come from? What am I? And where am I going?

Matisse set out for Tahiti just as he was recovering from a major illness for some reason feeling compelled to follow Gauguin’s path. I never understood the purpose of that trip until I read about it in Spurling’s biography of Matisse. He only took out his paints once, while he was on this several months-long trip, and that was to paint some of the foliage on the edge of the jungle. He sent a few sketches to his family, but nothing else. Yet when Matisse returned home, what he brought with him and what appeared in his work for years to come was the light of the Pacific.

What will I bring back from my medical journey? I spent six days in the hospital mostly meditating. I kept my eyes closed much of the time, so much so that there was still some glue on my eyes on the third day. I don’t know what visions were brought on by the painkillers and what by the meditation, but I do remember the pillows under my arms being encrusted with light-reflecting jewels.

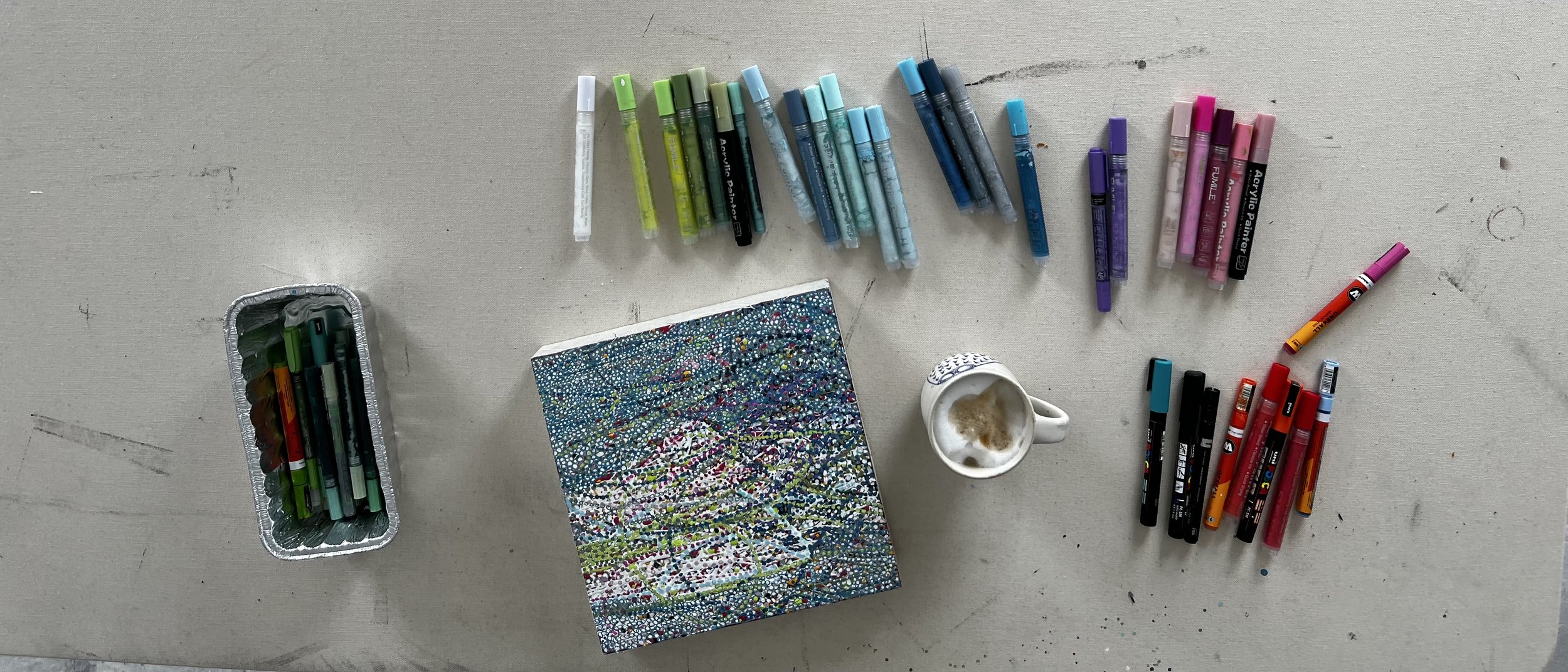

I tend to see limitations as challenges and not barriers. So, when I could not concentrate enough to work on a large painting, I started working on some very small paintings. I tried to distill everything I was doing in my large paintings into these small ones, some as small as 2 inches by 4 inches. I wanted them to be mesmerizing and full of detail close up and still have an impact from across the room. Throughout much of the year, these small paintings completely preoccupied me. For one thing, while they can take a disproportionate amount of time to produce for their size, it is still less time than a large painting. I can experiment and explore things more quickly – think of a Vespa motoring through the streets of Rome.

Read more about my experience of surgery here

See the full collection of small paintings here.

HISTORY SPOTLIGHT: PAIRINGS - Tobey + Pollock

-

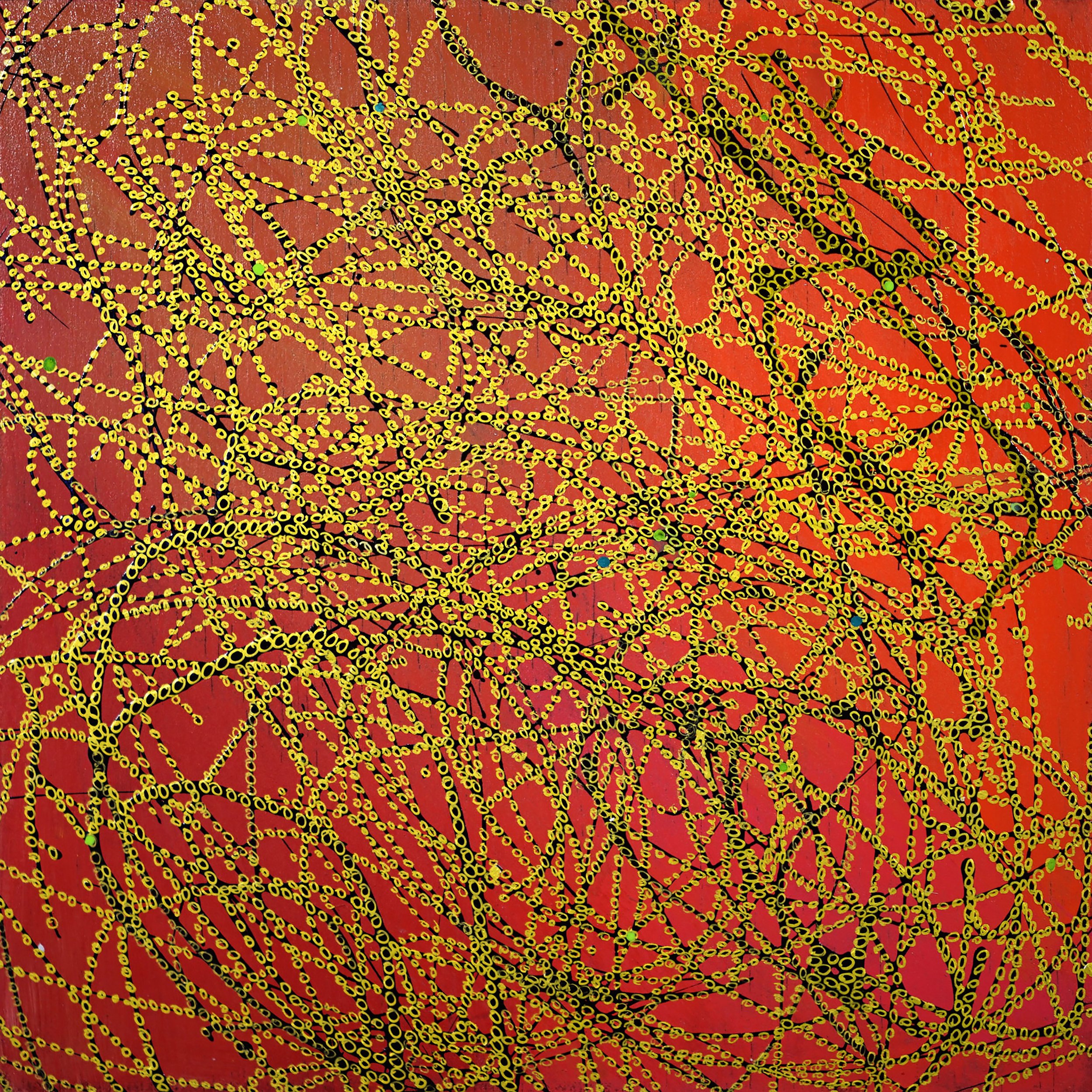

Elizabeth Bayley Willis showed Tobey's painting Bars and Flails [23] to Jackson Pollock in 1944. Pollock studied the painting closely and then painted Blue Poles, a painting that made history when, in 1973, the Australian government bought it for $2 million. A Pollock biographer wrote: "...[Tobey's] dense web of white strokes, as elegant as Oriental calligraphy, impressed Jackson so much that in a letter to Louis Bunce he described Tobey, a West Coast artist, as an 'exception' to the rule that New York was 'the only real place in America where painting (in the real sense) can come thru." [24] Pollock went to all of Tobey's Willard Gallery shows where Tobey presented small to medium-sized canvases, measuring approximately 33 by 45 inches (840 mm × 1,140 mm). After Pollock viewed them, he went back home and blew them up to 9 by 12 feet (2.7 m × 3.7 m), pouring paint onto the canvas instead of brushing it on. Pollock was never really concerned with diffused light, but he was very interested in Tobey's idea of covering the entire canvas with marks up to and including its edges, something not done previously in American art.[25]” [Wikipedia]

FROM THE LIBRARY : MATISSE THE MASTER

Hillary Spurling wrote “The Unknown Matisse,” about his early life and “Matisse The Master.” Both are fascinating. She was able to use archival materials that were not previously available. I love knowing the context in which artists create their work. This book covers the War years. I never knew, for example, that his daughter, Marguerite, ran messages for the Resistance in Paris, and was tortured by the Nazis for her efforts. Spurling gives great insight into his family relations, his relationship with his dealers and collectors, and the terrible toll his health took on him. While James Lord’s book on Giacometti, which I also loved, feels like a book written by an artist for an artist, Spurling’s book speaks much more to the historical context of the Matisse’s work.

ART SPOTLIGHT: Drawings from the 80’s

26 Jan 81 X

In the early ‘80s we had some dreadfully cold winters in Shushan; days when the temperature was 40 below. We were caught in an Arctic weather cycle that was relentless. You could not get warm. It was not possible to heat my studio, so I stayed home next to the wood-burning stove and I made small paintings on paper. Many of the concerns that appeared in these early pieces have resurfaced in my work years later. There were no rules. Just stay warm and keep painting.

See more of these small works here.