BLOG

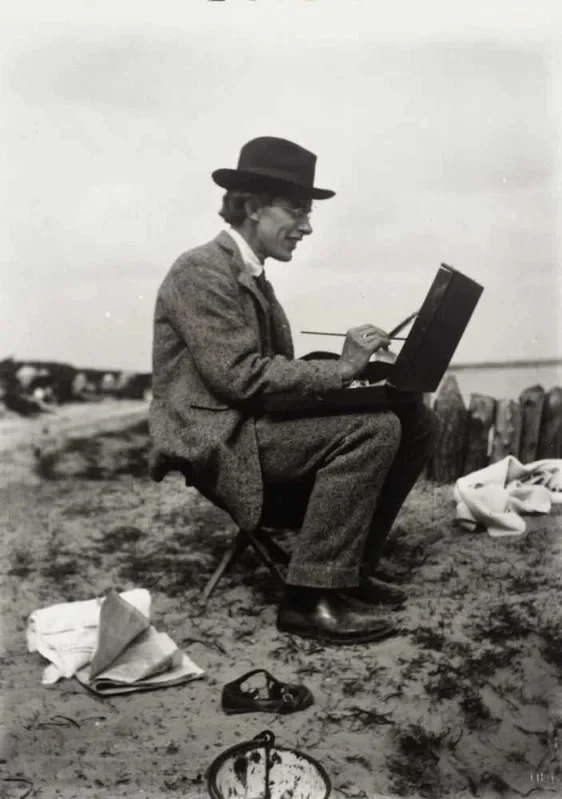

LOOKING WITH ROGER FRY

The first time I read Roger Fry, my immediate thought was: finally, someone who looks at a painting the way I do. Not emotionally first, not narratively, not in search of reassurance or uplift, but through a disciplined form of attention. What we now call formalism felt, in his writing, less like a theory than a discipline—a way of agreeing to stay with what is actually there. Fry’s focus on line, color, rhythm, and spatial structure was not a narrowing of meaning but a refusal to dilute it.

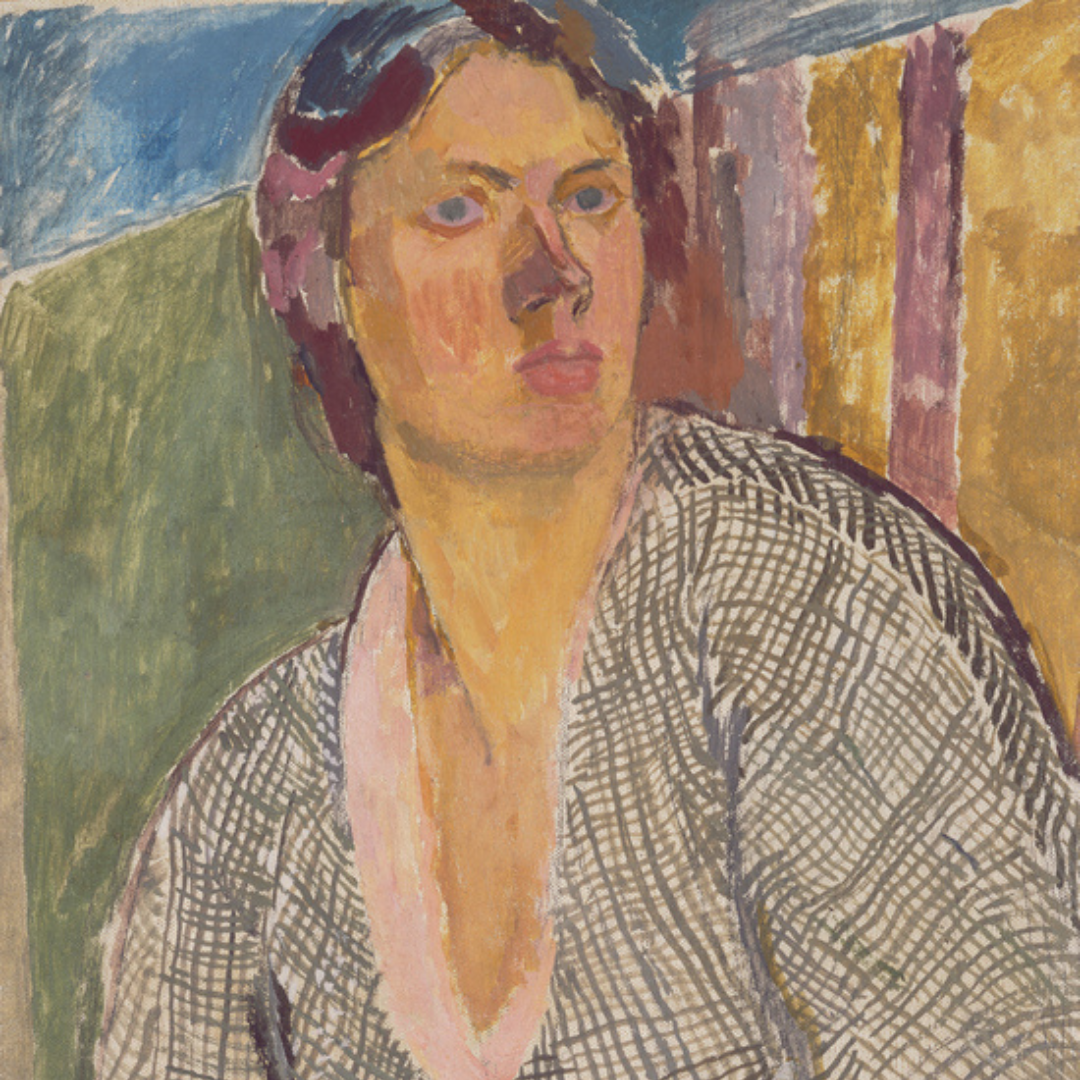

VANESSA BELL: LIVING THE TRUTH

Vanessa Bell did not set out to be radical. She set out to live honestly. The radicalism followed.

She believed that the way one lived mattered as much as the work one made, and that conventions—marriage, propriety, feminine self-effacement—were only useful if they did not interfere with the truth of daily life. When they did, she quietly stepped around them.

This was not a theory. It was practice.

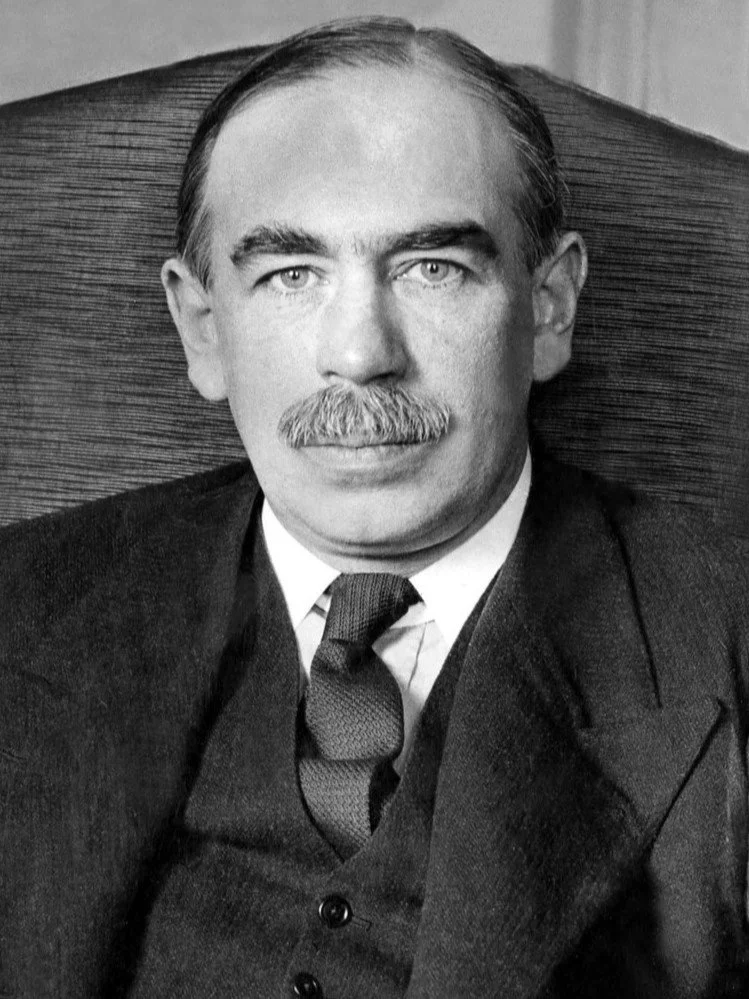

JOHN MAYNARD KEYNES: Economics with a Nervous System

John Maynard Keynes is usually introduced as the economist who saved capitalism from itself. That is true, as far as it goes. But it is not how he thought of himself, and it is not how he lived.

Keynes moved through the world less like a technocrat than like a man attentive to atmospheres—rooms, moods, confidences, collapses. His economics emerged not from abstraction, but from observation: how people actually behave when frightened, hopeful, reckless, bored. He did not believe that markets were rational systems tending naturally toward equilibrium. He believed they were made of people, and that people were volatile, suggestible, contradictory, and emotional.

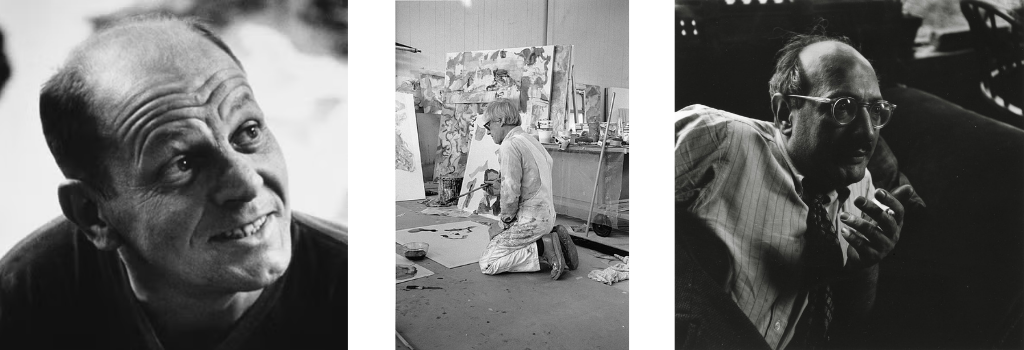

DORA CARRINGTON AND LYTTON STRACHEY: Love Without a Center

If Vanessa Bell built a life around coherence, Dora Carrington and Lytton Strachey lived inside a more unstable geometry. Their relationships were not anchored by truth-telling in the Bell sense, nor by the steady negotiation that held Charleston together. What animated Carrington and Strachey was something else entirely: intensity without reciprocity, devotion without symmetry, love without a shared object.

THE HANGOVER

Every story about artists and bars eventually needs a morning-after chapter. This is it.

It’s tempting to treat drinking as part of the atmosphere, like bad lighting or loud music. Something incidental. Something that belongs to the room rather than the body. And for a while, it does. Conversations loosen. Arguments sharpen. People stay later than they should. Work gets talked about intensely, if not always made.

But alcohol is not neutral. It never was.

THE IMPRESSIONISTS AT TABLE : WHERE THEY ATE, WHO PAID AND WHY IT MATTERED

Few things reveal the inner life of artists more than where they choose to eat once they finally have a franc in their pockets. For the Impressionists, dining was never simply sustenance—it was strategy, camaraderie, theater, and the occasional act of defiance. Their restaurants tell the story of their rise: from noisy cafés of argument to polished dining rooms where turbot arrived under silver domes.

FOOD DIPLOMACY: HOW MEALS HAVE SHAPED WORLD POLITICS

History is full of treaties written in ink—but many were sealed in sauce. "Food diplomacy" may sound quaint, but it has altered borders, changed empires, soothed enemies, and occasionally humiliated them. The table has always been a stage, and the meal a weapon or an olive branch. From Carême’s diplomatic cuisine to modern photo‑op hamburgers, the evolution of political dining tells us exactly how power works—and how it tastes.

THE SUN KING AT SUPPER: HOW LOUIS XIV TURNED DINING INTO POWER

If you have ever walked into a fine restaurant and felt a little smaller, a little more aware of your posture, or a bit uncertain about your knife, you may be experiencing the long shadow of Louis XIV. The Sun King did not invent haute cuisine to delight the palate. He created a world in which eating was a political act. The food was beautiful, but the real purpose was control.

NEW YORK CITY: ARTIST, BARS AND THE MAKING OF A SCENE

New York has always had two art worlds: the one in the studios and the one at the bar. The former produced the work; the latter produced the legends. If Paris had its cafés, New York had its dimly lit rooms with sticky floors, cheap whiskey, and artists who argued, seduced, collapsed, and occasionally painted the bathrooms.

Below is a guided stroll through the great artist bars of New York City — who drank where, who paid, what they ordered, and what survives.

SMALL ACTS, QUIET ACTS: Generosity Artist to Artist

Not all generosity is institutional.

Most of it isn’t.

Most of it happens off the record, without witnesses, without announcements, without plaques. It moves quietly, passed hand to hand, story to story, like folklore.

Kenneth Noland bought materials for Jules Olitski when Olitski couldn’t afford them. Jasper Johns carried Roy Lichtenstein’s work to Leo Castelli when Lichtenstein couldn’t bring himself to do it himself. Agnes Martin slipped younger artists envelopes of cash in Taos—or simply showed up at their studios and gave them her full attention, maybe the rarest gift of all.

IT TAKES A VILLAGE: When Community Makes Art Happen - Literally

This is how Music from Salem describes itself: Music from Salem brings together musicians of international reputation to prepare and perform chamber music in the peace and beauty of rural Washington County, New York, and environs. Chamber music is classical music written for a small group of performers and encompasses a range of styles from the 18th century to today.

THE VOGELS: HOW A MAILMAN AND A LIBRARIAN REWROTE THE STORY OF ART COLLECTING

In a moment when so many conversations about art circle around markets—prices, auctions, returns—it feels grounding to remember Herbert and Dorothy Vogel, a retired postal worker and a Brooklyn librarian who built one of the most remarkable collections of postwar art on a pair of modest civil-service salaries. Their story is often told as a charming oddity, but it is something far more instructive: a long, sustained act of devotion that reshaped the lives of artists, the stability of galleries, and the cultural map of this country.

COMFORT FOOD COMMUNITY — FOOD FEEDS COMMUNITY

When I think about what keeps a small town alive, I don’t think only of festivals or fundraisers — I think of the quiet networks of generosity that feed people, ground them in dignity, and hold them together. That’s what Comfort Food Community does in Greenwich, and it matters deeply.

ARTISTS WHO UNDERSTOOD WHAT ARTISTS NEED

The artists who created the major foundations of the last century were not marginal figures or cautionary tales. They were serious artists with long, complex careers — people who knew what it took to keep working through uncertainty, invisibility, and the strain of daily life. Their foundations exist because their work succeeded, not in place of it.

ARTISTS HELPING ARTISTS, Part 2: Built-In Generosity —The Communal Institutions

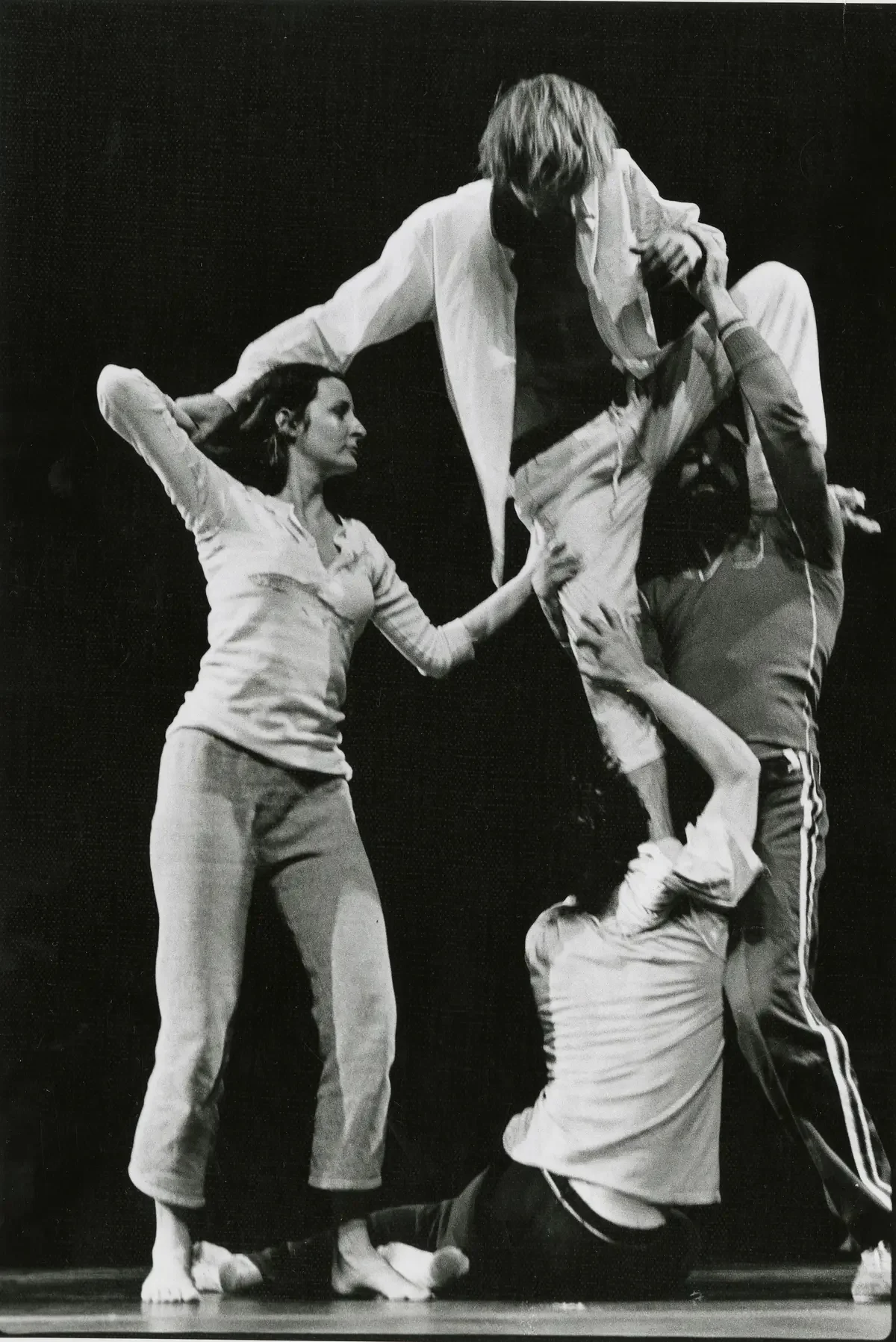

I was fortunate enough to study contact improvisation with Steve Paxton when he taught dance at Bennington College, and to participate in a dance workshop with Trisha Brown at the Whitney Museum’s Independent Study Program—the one summer it took place in New Mexico. So, it was no surprise to me to learn that Judson Church institutionalized generosity.

When dancing contact improvisation, you have to be completely attuned to the dancers around you. It’s a form where you literally feel your way through it—one person shifting weight, another offering balance, and both trusting that the floor, and each other, will be there. Trust is the foundation of this form of dance. People who understand this know that the welfare of those around you is intrinsically related to your own.

ARTISTS HELPING ARTISTS, Part 1:The Early Acts of Kindness

It is not a secret that I am obsessed with nineteenth-century French art, but so are most people with an avid interest in art. Besides the extraordinary work produced, the interpersonal relationships are also highly interesting, both the rivalries and the mutual aid. Monet could not have survived without Bazille; the Impressionists probably would not have been shown without Caillebotte. Rodin both helped and undermined Camille Claudel. And, of course, what would have happened to Van Gogh without Theo?

THE LINEAGE OF EXPERIMENT: From the Bauhaus to Bennington College to Woodstock Country School

I didn’t realize it at the time, but the schools I attended — Woodstock Country School and later Bennington College — were direct descendants of the Bauhaus experiment. Each believed that art was not a subject but a way of understanding the world. The lineage that ran from Weimar to North Carolina to Vermont shaped not only my education but the way I’ve made art ever since.

ARTISTS BEHAVING BADLY

I don’t want euphemism. I don’t want erasure. I can acknowledge unforgivable acts and still argue the work belongs in public, framed honestly. I don’t want the truth whitewashed, and I don’t want the art erased. The real discipline is holding contradictory facts in your head without sanding them down, letting the discomfort do its work.